07: Fear itself

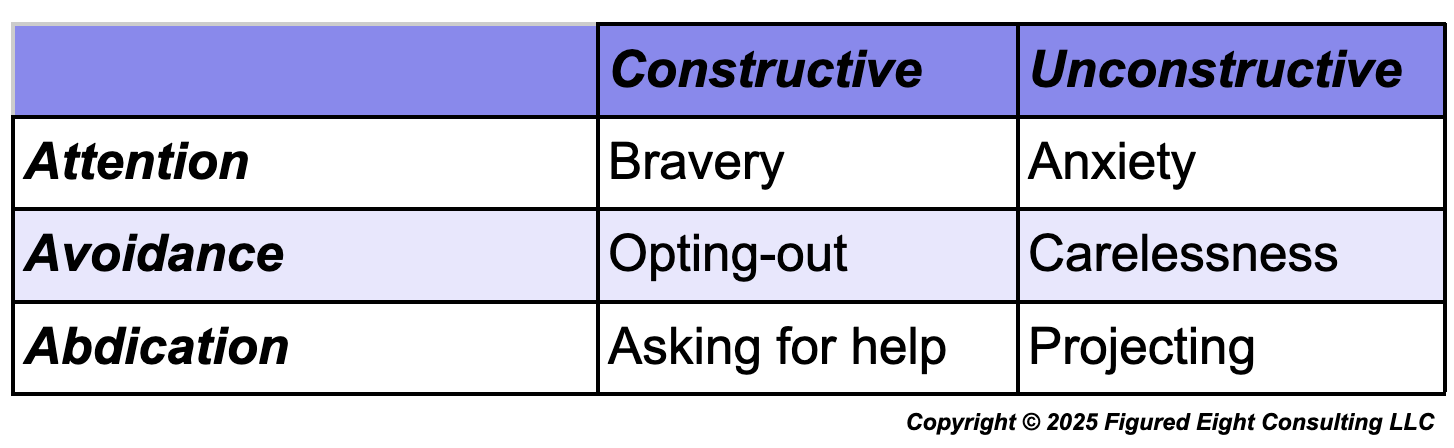

Constructive and unconstructive behavior in the workplace

When asked what he did each week, the exec explained that he worked on the things that scared him the most. Fear can be a powerful motivator and this got me thinking about where else I find myself and colleagues motivated by fear—of making (or repeating) mistakes, of being embarrassed, of failing, of not being good enough. I have bucketed behaviors in response to fear as attention, avoidance, or abdication and identified both constructive and unconstructive versions of each. While understandable on a human level, the unconstructive choices have negative impacts on others; in a company, these behaviors can threaten individuals as well as the stability and success of teams. My goal is to consider how to strengthen teams by mitigating and addressing unconstructive behaviors in the workplace and I begin by laying out some examples.

Attention: bravery and anxiety

In Ben Taub’s excellent profile of Bertrand Piccard, fear is described “as an irrational projection of a negative future scenario that, with sufficient focus and training, was unlikely to come about.” Engaging, with focus and training, with the thing that is scary can mitigate both the perceived risk and the actual risk. In the workplace, risk-based prioritization—tackling first the things that present the greatest risks—is a strategy for success. Key to this kind of attention is understanding the severity and the likelihood of the risks, such that the behavior and actions (even if not the feeling) are calibrated to the risk. This is one version of what I call bravery. It doesn’t mean ignoring the fear, nor does it necessarily mean taking on a risk; it means being deliberate and thoughtful such that action is not driven solely by the emotion.

The unconstructive version here is anxiety, which is when too much attention is paid to the fear and the attention outweighs action. (While I am using words that have specific meaning in fields that are not my expertise, I am using them colloquially here.) An anxious leader or team may call more attention to the statement of risk rather than to means of addressing the risk, getting stuck on the “what” rather than moving to the “so what”. An anxious leader may amplify, for their team, any uncertainty or churn that they hear above them. Someone who is anxious to not make mistakes may be inefficient in their work due to their concern about making things unnecessarily perfect. An anxious manager may micromanage, making work whiplashy for direct reports and silencing their useful voices. In all these cases, one person’s anxiety holds back the entire group.

Avoidance: opting-out and carelessness

At a recent puppetry show, we were taught that attention to anything can make it come alive. Perhaps that is why sometimes it is hard to give attention to fear. Fear is felt in the core and one way to avoid that is to simply opt-out. When I had an opportunity to bungee jump, I passed. While this was a lost opportunity for me, it didn’t impact my friends—they still did their jumps and I got to watch all the wild things their bodies did on the way down. I label opting-out as constructive because it is a clear decision and it includes taking responsibility for the reaction to fear. Opting-out can be the easiest thing to do and when the reward of taking the risk is not important to me, I am ok with that choice.

The unconstructive version of avoidance can put others at risk: carelessness. At a recent concert, I found myself behind two men too drunk to stand on their own. Yes, alcohol may relieve feelings of social anxiety, that fear of “what if someone thinks I am not good enough”. While it can feel great, as if carefree, to have awareness dulled, others can be impacted when the sense of social cues and physical boundaries is lost. At the concert, my attention was drawn from the stage to those men, watching them so as to protect myself in case they fell on me. Maybe they were having fun and they were being careless.

In the workplace, carelessness can show up as people taking shortcuts, such as not wearing safety glasses where needed. In particular when a leader is the one to do that (the exec showing investors around; the boss checking on progress), this carelessness can set an example that puts others at risk. I have seen grad students perplexed as to whether to follow their advisor’s cavalier attitude towards eye safety or to follow the known best practices. Such carelessness can also impact the company; a workplace injury can shut down a lab for a period of time or threaten an entire business.

Carelessness may also show up as the person at the office party who hits on colleagues after enough beers to not feel shy; the boss who shrugs off employees’ concerns about physical safety, discrimination, or psychological safety; the colleague who uses “ruinous empathy”; the culture that prioritizes speed above considerations of the impact of breaking something. These kinds of carelessness erode trust and can also decrease both the real and perceived safety of others. When I am brushed off by someone careless, I am more likely to pay attention to the risk as I do not trust the person who has given me an empty “it will be fine”.

Abdication: asking for help and projecting

Sometimes people ask others to carry some of the weight of confronting things that feel scary. The constructive examples are asking for help and they come with some shared understanding (albeit sometimes with a very clear power dynamic or a transactional relationship). The person who asks a friend to remove a scary spider—they are asking for someone else to take on the risk they don’t want to take. Ditto for the person who hires someone else to go to the grocery store for them during a pandemic. Or the person who opts-out of social media and asks a friend to show them posts to avoid missing out. In all these cases, the person is abdicating some responsibility, asking for someone else to take a risk for them. In the best version of this, it builds connection between the person who asks for help and the person who provides it. The personal example that first comes to my mind is from hiking. I am always nervous about stream crossings—you can see it in my posture in the picture below. I tell my companions this in advance and ask for help at the time. Maybe someone else goes first or someone waits a minute for me. Hopefully we all feel better about each other with that communication.

Asking for help can require a humility and a self-awareness, another kind of bravery. I am humbled and grateful when friends or colleagues let me know they are scared and ask for help; it enables me to better understand and engage with what is happening. In workplaces with psychological safety and healthy culture around collaboration and communication, people find it easy to ask for help.

In the unconstructive version of abdication, the fear is not named and there is no shared understanding. In ‘projecting’, someone takes out their fear on someone else, displacing the impact. This is a protective strategy that can be quite disruptive, even harmful, to others. In an extreme, it can be bullying. Here are some workplace examples:

the boss who manages embarrassment about poor typing by not responding to email (without explanation) so the team is left waiting and confused

the person who responds to a sense of discomfort around people who are “different” by avoiding tasking them, inviting them, including them; the colleague labeled as “different’ is thus unable to participate, contribute, succeed as much as their peers

the boss who finds it scary to be challenged and thus fires the forthright junior employee

the minority group that is counseled to be less visible so as not to trigger someone’s social fear

the person who is afraid to question the boss and instead chatters with peers about their concerns, spreading a sense of unease without addressing anything

the person who is afraid to be wrong and thus does not show their work for review

the person who is afraid to expose their confusion and thus persists in their work with misunderstanding

the person who is uncomfortable addressing their own fear and thus mocks or critiques anyone who pays attention to risk

the stakeholder who pushes the team to low-risk mediocrity because their own self-interest makes them hope the company is risk-averse

the person who deflects attention from their own work or emotional response by over-explaining to or solutioning for others

the team leader who is afraid of making the wrong decision and thus does not make clear decisions.

All of these put the responsibility on others—without consent—for someone else’s fear, turning one person’s fear into another’s problem. The list above includes examples of social (not physical) fears and projection of social fears may be more likely to occur in a workplace that lacks psychological safety. Moreover, these behaviors can breed an environment of low psychological safety, where people are less likely to speak up or speak out or ask questions. This limits a company’s ability to do excellent work, to retain good people, to grow, to innovate.

Management

In a conflict resolution class long ago, we were taught to replace defensiveness (a kind of projection) with curiosity. In a different context, replacing fear with curiosity was named as a key to living a creative life (one that isn’t always opting-out). For managing my own response to fear, I aim to bring curiosity to myself and the situation, to recognize the emotion and make thoughtful choices based on realistic possible outcomes. For the things that matter, I aim to be brave or ask for help and I don’t always get there.

To mitigate carelessness in my group as a manager, I’d set clear expectations and responsibilities. I’d hold accountable on short time scales a person who showed carelessness. I would make sure the team culture celebrated not just the heroics of solving a problem but equally the thoughtfulness and hard work that goes into taking care to reduce the occurrence of problems. I would look for opportunities to make structural changes to mitigate carelessness, such as putting a hand-washing station at the exit to a lab or making company socializing less centered on alcohol. In response to observed careless behavior, I would first act quickly to address safety concerns and then address responsibility.

To mitigate the impact of an individual’s anxiousness on the group, I would look for opportunities to pair people as peer mentors so that constructive styles of managing fear could be shared. I would make sure everyone had both information and agency to address risks that would impact them. I would aim to bring curiosity and compassion to folks and to be ready to show them how the company is appropriately managing risk. I would listen to their concerns or give them a place to be heard, both for their sake and to make sure the company would have a chance to hear if an individual picked up on something that was otherwise missed. I might look for company practices—such as anonymous feedback forms and pre-mortems—that can help serve this purpose of giving people a chance to have their concerns heard. At one company, a direct report was so anxious about their ability to do their new job that they were thinking about quitting (to stave off fear of being fired). My listening was impactful enough that they stayed, performed well, and later thanked me for this intervention. On the receiving end, I have also experienced mere listening as a powerful tool.

If I was managing someone who seemed to be insecure and projecting on others, I’d double down on clear expectations, priorities, and lines of responsibility and accountability. I would also try to bring curiosity to the insecure person to see if we could address the core needs directly. I would encourage the person to look for ways to shift to the constructive behavior of asking for help. I would also look for ways to support people who might be on the receiving end of this projection.

In all these cases, I can imagine scenarios in which unconstructive behavior would indicate a need to find someone an off-ramp, to better ensure their success or for the sake of the company.

Managing up is a different challenge. If other leaders showed a continuing pattern of carelessness or insecurity that they then projected on others, I’d be concerned for myself, for my colleagues, and for the company. I’d prioritize first physical safety, even if that meant stopping work. After physical safety, I’d think about the psychological and professional safety of those on my team and of myself. I might learn about legal rights. I’d take notes. If I was up for the professional risk, I’d look for opportunities to speak up about my concerns. I would start looking for an off-ramp.

Bridging gaps

Difference in styles (attention vs. avoidance) or in assessment of risk (does this risk matter) can lead to disconnection and conflict between people. I think of how I was taken aback to learn that a friend who hosted game nights would only play games they were good at—their avoidant style of managing their fear of being incompetent was unfamiliar to me. Similarly, some new hiking companions were offended when I inquired, before heading into the winter wilderness, if everyone had raincoats—my attention was different than theirs. In both situations, these differences were stressors on the friendships. To someone who is being avoidant in a situation, the person who is being attentive may seem highly irritating. On the other hand, the person who is being attentive may feel ignored, unseen, or unsafe around the person who is being avoidant.

While writing this has given me a handle and vocabulary for thinking about these scenarios, I will continue to learn about how to not just name but also productively bridge these gaps on a team to facilitate effective collaboration. I’m wondering if the abdication styles are summoned sometimes in those gaps; by asking for help, an avoidant person may be able to connect with an attentive person in a way that serves them both. If instead, one person projects their own discomfort onto the other person, disconnection is the result. The next time I encounter a situation where my assessment of or behavior with respect to risk is different from a collaborator’s, I will start by naming it and look for ways to use our larger set of constructive strategies to make us stronger as a team.

Side notes

I recently stumbled upon Karin Anell’s Wall of Fear. Staring at the scrolling screen as long as the rain outside demanded, I noticed: teenagers with fear of social rejection; middle-aged folks with fear of loss of love or loved ones; and people who are scared of spiders. That was a nudge to write this.

When I consider times I have acted out of social fear, I tend to regret those choices.

My personal experience suggests there are societal differences across groups in how one’s concern about a risk is likely to be treated, who is expected to be anxious or brave, who is labeled as anxious or brave, and who is “allowed” to “worry”. (Surely, there is plenty written on this and I am not a student of the literature here.) I particularly reject exhortations of “don’t worry” if they don’t come with a reason that demonstrates care rather than carelessness. “Don’t worry if it rains, I closed the rainfly before we left and we each have raincoats” is different from “don’t worry if it rains, I’m sure it will all be fine.” Even better, generically, is curiosity: “tell me more about your concern so we can address it”.

Sometimes fear is an indication to me (especially if it is social fear or fear of failure) that there is something important to learn or gain on the other side. Sometimes I examine the situation and decide “I shouldn’t do the thing” or “I need to mitigate this risk”. Sometimes I decide “this fear means this is something that is important for me to do.” Examples of the latter include: nerves before a performance or a race; the denial fear of going to the doctor (like to see if this limb is broken). Starting this newsletter is another example. Thank you for reading.